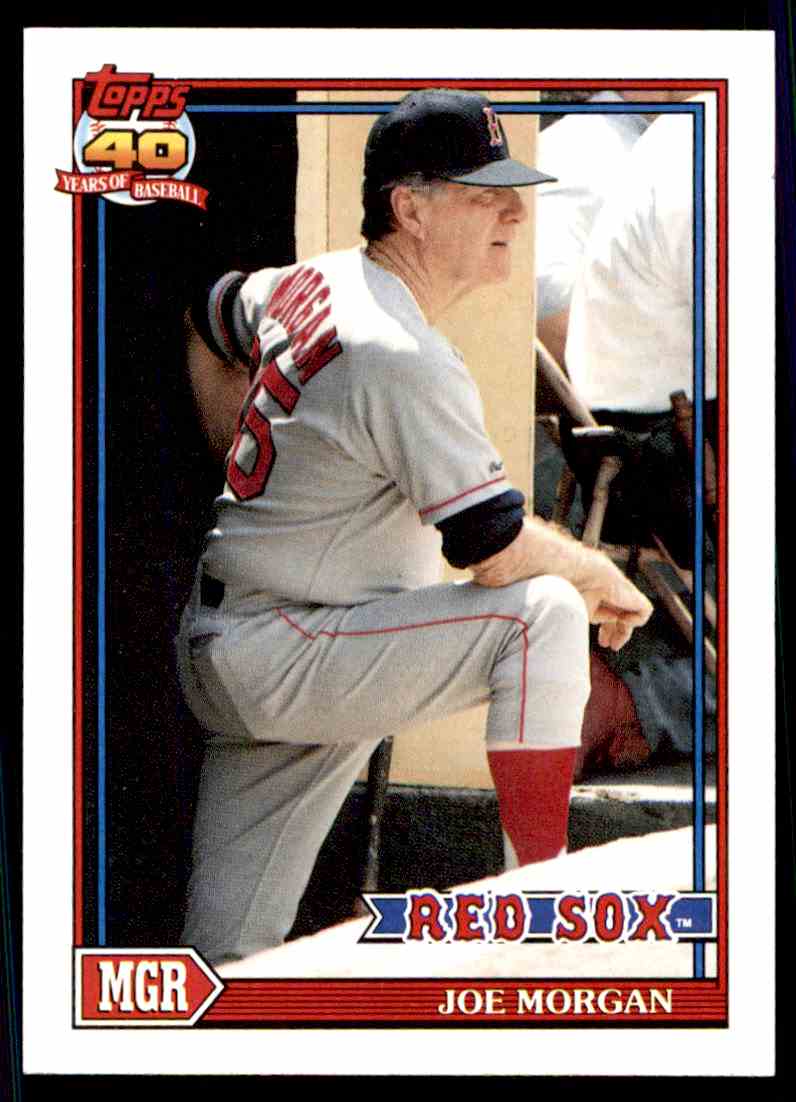

Last week, I received this baseball card from the Baseball Card Bandit (BCB). Included with this card was a note printed on a missed message piece of paper. The note said, “Til we meet again for the first time.” I know that I alluded to this with the Terry Francona card from last week, but it appears to me that the BCB is all done.

I know that the next question is, why? I think that the reason why is because the identity of the BCB was clumsily revealed to me two years ago at my brother’s wedding. While the name of the person was never verified, I think that he got the message that I know who it is. I’m not trying to be a tease, but I will not reveal the name until he is verified and he wants me to.

If the game is over, I am legitimately bummed out about this. This has been a fun few years of getting random baseball cards, writing about the players on the front of the cards, exploring how baseball relates to life and how perceptions change over time. How you might look at a player one way in 1988 and then see that person in a completely different light in 2019.

One of those players is the card that I received today, Joe Hesketh. If you think about Joe Hesketh at all—and aside from a username on SoSH it’s been a while since his name has invaded by cerebral cortex—mostly you might remember him as a fourth starter for some mediocre Red Sox teams.

And aside from his first full year in Boston, that’s who he was.

The 1991 season was a bit underrated in terms of interesting Red Sox seasons. They finished in second, behind the division-winning Blue Jays after completely falling apart late in the season. On Sunday, September 22, the Sox had two outs in the ninth against a bad Yankees team. Roberto Kelly was facing Jeff Reardon, who was protecting a one-run lead. Kelly loses the ball over the Wall and the Sox can’t score in the bottom of the ninth. Punching bags Matt Young and Dan Petry come in (there was no one left in the pen, I assume) and gives up two runs to the Bombers. The Sox bat in the 10th and Mo Vaughn rockets a two-out double, Jack Clark strikes out against Steve Farr and the Sox lose.

This was the turning point of the season as Boston tailspins into a 3-10 record, which costs Joe Morgan his job. The Red Sox were pretty brutal in the next three seasons, finally bouncing back in the strike-shortened 1995 season.

In 1991, Hesketh was pretty good swingman for the Sox. He appeared in 39 games, started 17 and went a career-high 12-4, with a 3.29 ERA with 104 strikeouts in 153.1 innings pitched. He also led the entire league in winning percentage (.750) that year, which is god damn amazing, if you ask me. If the Braves thought that he’d be this decent, they never would have released him in 1990.

Confession time: I used to get Hesketh confused with another mediocre lefty National League reject named Joe from around that time, Joe Price.

This was it for the former Montreal Expo (side note: he was 10-5 for the Expos in 1985, which happened to be his rookie year, good for eighth in the ROY award) in terms of being a serviceable pitcher, as his next three years were pretty poor. The good news for Hesketh is that he had his career year at the best time for the perfect GM in the league, as Sox General Manager Lou Gorman felt that he had to sign him and gave him a three-year, $5.1 million-dollar deal. For that scratch, Hesketh rewarded his team with 19 wins and ERAs of 4.36, 5.06 and 4.26.

I know that I’ve said this before, but it’s not the money that you give to the superstars that gets you fired, it’s the cash you dole out to the Joe Heskeths of the world. Gorman should have known that you can find a Joe Hesketh on every MLB roster and that he’d cost you nothing to aquire him. Also, Hesketh was 32-years-old in 1991, he wasn’t going to get better as he got older. And it was pretty obvious that he was going to get worse.

I’m not saying that the Hesketh deal was what Gorman axed at the end of the 1994 season, but this—along with the rising star of Jeff Bagwell in Houston—had to be on the list. Joe Hesketh was a one-man heist movie.

And while he pretty much stole $5 million from the Red Sox, good for him. The Sox should have known what they had in Hesketh, they shouldn’t have given him anything more than a one-year deal. If they wanted to give him a 1992 contract for $1.7 million in recognition of a good 1991 season, so be it. But there’s no need to get attached to a guy like this for real money.

That’s all on Gorman.

I think that’s something that fans need to understand. A player is going to get as much money as they can. Teams need to have some sort of foresight and intelligence when it comes to deals like this. If they can’t help themselves, that’s their problems. I never understood why fans take the teams’ side when the teams gave out the contract.

Oh well, I guess that’s as good of a rant as anything to go out on.

In any event, it’s been a fun couple of years and hopefully I’ll get more cards. But if I don’t, I guess I’ll have to come up with a new project for me to write about and for you to read. Talk to you soon!